Giuseppe Tucci, an Orgiastic Aha! Part One

By Joseph Houseal | 2017-12-08

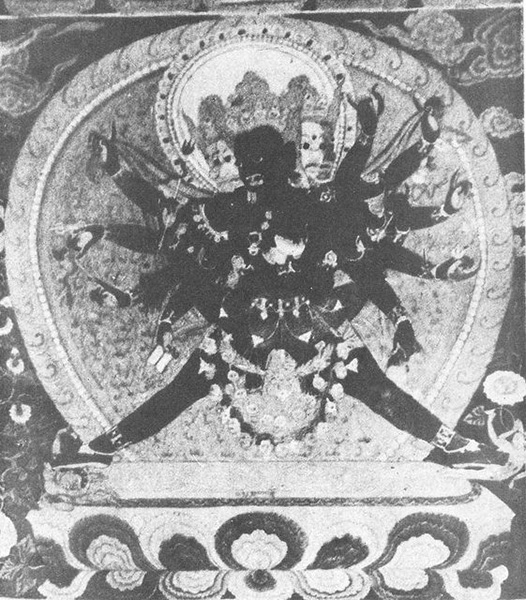

Protector of the Dharmakaya, 17th century, Tsaparang, Tibet. From Tucci, Indo-Tibetica lll.2, Reale Accademia d’Italia, 1935. Rome. Plate IV

Giuseppe Tucci (1894–1984) was an Italian scholar-adventurer who supervised archeological digs in Iran, Persepolis, and the Himalayas. He was fluent in ancient and modern languages of East and West, and is considered the father of Tibetan studies as well as Buddhist studies, based largely on his several expeditions into Tibet and the resulting research and presentation woven into his professional teaching. His level of originality and scholarship is staggering. His ability to appreciate art, examine the past through exploration, grasp whole world systems and imagine others, distinguishes his vast legacy from other more typical scholars who rely too much on literature for cultural understanding.

Tucci traveled in Tibet exploring pre-Tibetan Zhangzhung culture, as well as Tantric Buddhist culture, some intact, some in ruins. Like other early explorers, pioneers who established contact, Tucci relied on his intuitions and posited great conceptual underpinnings of Asian thought in contrast to Western systems. Tucci was unafraid to surmise, to project; to know what he did not know so he could come to know it. What a delightful surprise to see that Tucci brought the full force of his intellect and intuition to bear on perceptions of ancient Buddhist and pre-Buddhist dance. He was interested in origins and how pre-Buddhist concepts and energies filtered into Vajrayana Buddhism.

This three-part article focuses on Tucci’s perception of dance in mural paintings, specifically his use of the word “orgiastic” to describe tantric deities dancing while coupled in erotic union. My own research into Tucci and this term he applied resulted in new perceptions of deities, tantra, and dance. This first part will introduce Tucci and share a couple of the passages in which he uses the term. In parts two and three, I will analyze more thoroughly the term, the deities, and the implications.

I’ve been called a paleo-choreologist. The search for dance backwards in time reviews the literature, examines archeological evidence, studies the artistic representation, and above all examines extant dancing. Tucci did all these things. Many of the early Western explorers of Tibet were judgmental about the dance they encountered. Surely ignorant, they mis-represented the dances as pagan mummery. Few connected the dances they saw to the artistic expression of Buddhist teachings, even though they are the very same things. Consequently, we have a Western art scholarship treating Tantric Buddhism in a most dry, lifeless way, reflecting the Western bias against dance that extends back to the 3rd century and the rise of the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas, wherein the body is sinful. In Tantric Buddhism, the body is the vehicle for enlightenment. Tucci saw that art history and dance history illumined each other, that there was indeed a religion inside a religion.

An engraving of the Hemis Monastery Cham festival, produced from a pencil drawing of the live event. 19th century, England. Courtesy of Hemis Monastery Museum. Nearly every aspect of the Cham dance is incorrectly recorded. That the Cham is circular is correct

The early explorers included botanists, surveyors, military commanders, soldiers, doctors, missionaries, and political leaders of the British Empire. There is so much to learn from those who got it all wrong. The best early descriptions of Buddhist Cham dance come from L. A. Waddell, who condemned it entirely. There is a British engraving of Hemis Monastery Cham, in which nearly every aspect of the dance is incorrect. I gave it to Hemis Monastery Museum where it now hangs.

It is thrilling to encounter an early explorer who not only got it right, but asked provocative questions about the nature of dance in ritual Buddhist paintings. Tucci saw the dance as essential to understanding Tantric Buddhist art and the deities and characters depicted. Not only does he point out that a class of dakinis dance with wrathful deities, but he goes to lengths to describe and define the rarified nature of the creatures who are dancing. It explains in part the role of dance in meditation technique to know exactly who they are, that are dancing in a meditation; and when, in the process of meditating, they appear.

Part of what makes a Cham dancer of deities is being a monk first, acquainted with the rituals and iconography, as well as the meditation techniques of Tantric Buddhism. That is who dances Cham. To understand the dance, you have to understand the monk. Tucci saw that to understand the dance in art, you have to understand to what class the deity belongs, how visionary and alive, how immanent and evanescent, how connected to profound progressive mental conceptions. In Tucci’s writing, I have encountered ideas about dance in Tantric Buddhism that I’ve encountered nowhere else. Tucci discusses why and how the feminine dakinis dance differently than the monstrous wrathful deities. In so doing, he reveals a quintessential tantric skill of uniting gnosis to praxis.

Chakrasambhava coupled with Vajrayogini, representing wisdom and compassion as aspects of the same primal energy. The pose is unusual as Vajrayogini is standing with both of her feet on the ground. Chakrasambhava’s legs are white and red. The five elemental colors comprise the composition: blue, white, green yellow red. Tibet, date unknown. From Core of Culture

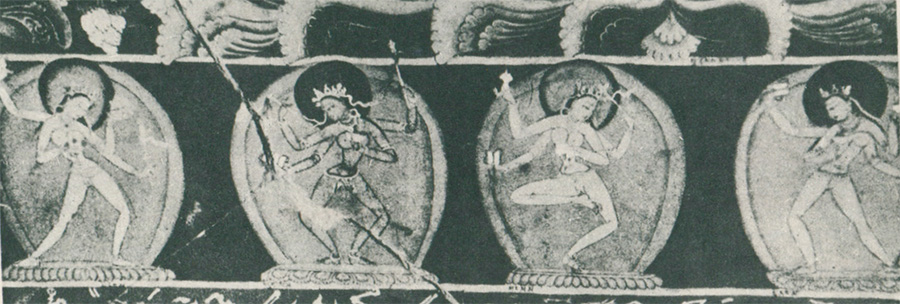

Top to bottom, left to right: Padya, Arghya, Puspa, Dhupa, Dipam Ghanda. Dakinis dancing a “living cadence.” 17th century, Tsaparang, Tibet. From Tucci, Indo-Tibetica lll.2, Reale Accademia d’Italia, 1935. Rome. Plates IX, X

“Everything in this art has symbolic value and meaning, from the colors, to arms, and to instruments in the hands of the deities, from the ornaments by which they are covered to the orgiastic dance that most of them dance in the rapture of the embrace. . . . This is not the moment to insist on the complex symbolism of these figures. They, in my opinion, have a beauty which is their own; a grotesque beauty if you will, but nevertheless a sure power of expression . . . an impressive and efficacious representation of that uncomposed world of tumultuous forces in creation and in the human subconscious . . .”

“We are faced by an attempt to reproduce pictorially states of the soul, spiritual impressions and motifs, that no other art has known how to inspire such a variation of forms. . . . We see the domination of the rhythms of the dance, not always so graceful and sweet as in the small figures of the feminine deities, constituting the train of Samvara . . . but more often violent and orgiastic as in the type of coupled deities. In the first case, the thin legs posed in different positions for each figure, seem to convey almost the idea of a living cadence, in a manner that by running over the image with the eye, it seems that this delicate pictorial procession in animated and moves to the rhythm of a mystic dance, as if coming to new life by mystical evocation.”

Mahasuka-daka dancing coupled with his Dakini. Mural painting. The dakini’s legs are wrapped around the waist of the deity, whose legs, fully splayed, perform a tantric dance requiring extreme skill and control. 17th century, Tsaparang, Tibet. From Tucci, Indo-Tibetica lll.2, Reale Accademia d’Italia, 1935. Rome. Plate XXlll