In the Land of the Dead, Stepping on the Tail of a Rainbow (detail), by Takashi Murakami. 2014, acrylic on canvas; The Broad Art Foundation, © Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

From Manga to Monks, Anime to Arhats: Recent Buddhist Themes in the Art of Takashi Murakami

By Meher McArthur | 2016-04-16 |

Japanese artist Takashi Murakami has become renowned internationally for his colorful, smiling flowers, his anime-inspired paintings and sculptures that range in style from erotic to ominous, and his controversial collaborations with the fashion industry and music icons. A highly successful figure in the international contemporary art world and a powerful force in shaping Japan’s contemporary art scene, Murakami originally trained in traditional Japanese-style painting known as Nihonga, and in recent years has been drawing increasingly from his country’s rich artistic heritage to express his hopes and frustrations about modern society. In the last few years, he has selected themes and motifs from the realm of Buddhist art as tools for expressing the harsh realities of our world.

Murakami began making direct references to Buddhist art in his work in 2007, the year of the ©Murakami at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) exhibition in Los Angeles, the same exhibition that contained a fully functional Louis Vuitton store. At the same time as he was blurring (or “changing,” he asserts) the lines between art and commerce, Murakami was also bringing together aspects of traditional Buddhist iconography, folklore, and pop imagery. For this exhibition, he completed his first massive Oval Buddha, a towering statue in aluminum and platinum leaf more than 18 feet high. The figure borrows several iconographic details from traditional Buddhist sculpture, such as half-closed eyes, the pose of royal ease, the open lotus pedestal, and a precious metal finish denoting divinity. However, he has explained that the original inspiration for the figure was the nursery rhyme character Humpty Dumpty, so Oval Buddha is more a product of folklore than philosophy. Also apparent in this figure are references to Japanese mythical creatures—the flat, spikey hair recalling the head of the kappa, terrifying water imps who were believed to pull humans and animals into rivers, and the many eyes on its surface recalling hyakume, legendary monsters covered with 100 eyes who protected Japan’s shrines from thieves. With its oversized head, double face with frog-like features, spikey fangs, and goatee, Oval Buddha also draws from Murakami’s own personal artistic iconography, in particular from his character, DOB, a large-headed figure that is at once cute and menacing and features in many of his paintings and sculptures.

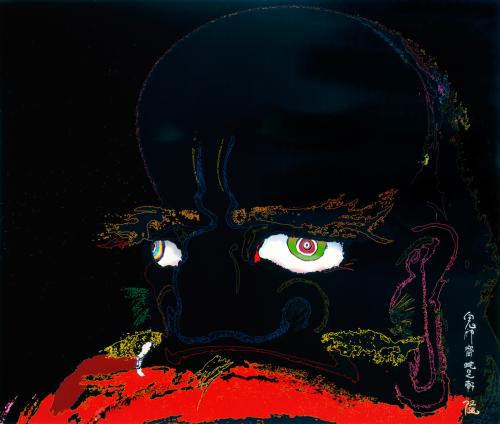

Also introduced in 2007 were some of Murakami’s first portraits of the Buddhist monk Daruma (Skt: Bodhidharma), the founder of meditational Buddhism, known in Japanese as Zen. Though rendered in acrylic and platinum leaf on canvas with vivid color accents, these bold, cartoonish portraits are faithful to traditional representations of the legendary Buddhist monk by Japan’s most renowned Zen artists. They even bear Japanese inscriptions, artist seals, and titles that recount Daruma’s legendary devotion to his meditative practice. Portrayed with firm, rugged brushstrokes as a grumpy-looking old man with large bulging eyes, Murakami’s Daruma images evoke the monochrome portraits of Zen masters Hakuin Ekaku (1686–1768) and more recently Nakahara Nantembo (1839–1925), both of whom took a whimsical approach to depicting this important Buddhist patriarch, one which was by no means irreverent since Zen Buddhists have long disregarded icons as a means to attaining enlightenment. Rather than objects of worship, such images serve as a reminder to Zen practitioners of Daruma’s determination to attain enlightenment through meditation; his large eyes and intense gaze recall the legend of the monk cutting off his own eyelids to prevent himself dozing off during meditation.

Oval Buddha Silver, by Takashi Murakami. 2008, sterling silver; The Broad Art Foundation, © Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

In his explorations of the image of Daruma, Murakami has varied the color of the monk’s face considerably in his series of portraits, sometimes painting it completely black, so that only the monk’s large, staring eyes are clearly visible, as in the haunting example in the Broad Art Museum’s collection. In 2008, at the Gagosian Gallery in New York, Murakami displayed a series of similar Daruma images in a row, an arrangement suggestive of repetitive screen-printed portraits of Andy Warhol, and one that playfully brings together Zen and pop art.

My arms and legs rot off and though my blood rushes forth, the tranquility of my heart shall be prized above all. (Red blood, black blood, blood that is not blood), by Takashi Murakami. 2007, acrylic and platinum leaf on canvas mounted on board, signage in platinum and gold leaf; The Broad Art Foundation, © Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Since the Tōhoku tsunami, earthquake, and nuclear meltdown of March 2011, Murakami has featured Buddhist imagery more centrally in his work. In his 2012 masterpiece The 500 Arhats (Japanese: Gohyaku Rakan), Murakami spotlighted the 500 arhats, a group of monks considered to be protectors of the Buddha’s teachings. This monumental painting with a deeply Buddhist theme was created as an artistic act of gratitude to the State of Qatar for sending aid to Japan so quickly after the devastating earthquake. With the assistance of 200 students, Murakami created what is probably the largest painting ever made, measuring 100 meters (328 feet) in length and designed to wrap around an entire large gallery space. The painting, recently displayed to great acclaim at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo, offers a powerful contemporary interpretation of a theme with a significant history in Japan Buddhist art.

According to Buddhist tradition, the arhats were disciples of the Buddha in India some 2,500 years ago and helped formulate his teachings after his death. While these monks are venerated as enlightened beings in the Southern Buddhist schools, they are considered less important than the bodhisattvas in the northern traditions of East Asia. Nevertheless, they are revered for having transcended the mundane world and are represented widely in East Asian art, typically as wizened old men accompanied by child attendants or animals. Though often depicted in groups of sixteen or eighteen, groupings of 500 arhats date back to the 12th century in Japan, when a Kyoto temple commissioned a set of 100 scrolls depicting the 500 arhats. Five centuries later, the grouping gained in popularity in Japan under the influence of Obaku Zen Buddhist monks, who had fled China after the collapse of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). The school emphasized the humanness of these holy men, and in 1695 built the Temple of the 500 Arhats (Gohyaku Rakan-ji) in Edo (modern Tokyo) and displayed 500 lifelike arhat statues in its grounds, drawing large crowds. Interest in the legendary figures continued and many temples commissioned images of these holy men to illustrate the redemptive powers of Buddhist teachings. In 1854, Zojo-ji, a Pure Land Buddhist temple in Tokyo, commissioned artist Kano Kazunobu (1816–63) to paint a series of 100 scrolls depicting the 500 arhats in idyllic natural settings and scenes of hell. In 1855, the Great Ansei Earthquake struck the area around modern Tokyo, causing fires and a minor tsunami that killed 7,000 people and destroyed 50,000 buildings, undoubtedly inspiring many of the violent, hellish scenes in Kazunobu’s paintings.

Kano Kazunobu’s 500 Rakan (arhat) scrolls were displayed together at the Edo-Tokyo Museum in the spring of 2011 to commemorate the 800th anniversary of the death of Hōnen (1133–1212), founder of Japanese Pure Land Buddhism. The timing of the display was particularly powerful just two months after the horrors of the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown. According to the Broad Art Museum’s website, it was Kano Kazunobu’s series of scrolls that inspired Murakami to create his own version of the 500 arhats. Created on a huge scale, the painting bursts with color, the bold backgrounds representing the colors of the four celestial directions in Buddhist and Daoist beliefs (blue for east, white for west, red for south, and black for north). Along the length of the painting are fierce demons, mythical beasts, as well as guardians of the four directions: tiger (east), dragon (west), phoenix (south), and tortoise (north), all set against vivid scenes of nature’s destructive power, lashing out in branches of jagged flame, or huge, swirling waves. Standing unshaken like pillars of hope are large- and small-scale arhat figures, portrayed with facial expressions ranging from grins to grimaces and arranged in groups, some facing each other, others gazing out at the viewer. Here, Murakami has created a monumental portrait of life, nature, and mortality in which the ancient figures of arhats, frail but resolute, suggest the power of prayer, spirituality, and community to help deal with the turmoil, horror, and chaos that humans must continually face.

Single scroll from The 500 Arhats, by Kano Kazunobu. Late 1850s, ink and colors on silk; Collection of the Zojoji Temple, Tokyo. From wikimedia.org

The 500 Arhats [The White Tiger] (detail), by Takashi Murakami. 2012, installation view: "Takashi Murakami: The 500 Arhats," Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2015, Photo by Takayama Kozo, ©2012 Takashi Murakami/Kaikai Kiki Co., Ltd. All Rights Reserved.